Nigeria’s health sector is facing a slow-burning crisis that is finally too obvious to ignore. Hospitals across the country are steadily losing their most valuable asset — trained doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals — to the lure of better opportunities abroad. The now-popular term "JAPA" perfectly captures the urgency and scale of this mass exodus, but beyond the slang is a deeper question: why are our health workers leaving, and what can be done to stop it?

The answer, sadly, is clear — and it isn’t new. The factors driving this brain drain have been years in the making. Health workers are not running away because they lack patriotism; they are fleeing an environment that has for too long undervalued their contributions, ignored their welfare, and failed to meet its promises.

According to the National Association of Nigerian Nurses and Midwives (NANNM), over 15,495 nurses have left the country in recent years. Similarly, the Coordinating Minister of Health, Prof. Muhammad Ali Pate, confirmed that at least 16,000 doctors have exited Nigeria within five years. These are staggering numbers, especially when you consider the cost of training a medical professional, the years of knowledge lost, and the void left in an already fragile health system.

Why Are They Leaving?

The reasons health workers leave are rooted in a system that has consistently failed to deliver on its obligations. Low wages, poor working conditions, outdated equipment, stalled career progression, and unimplemented court rulings on health sector welfare have combined to create an atmosphere of frustration and hopelessness.

Take the example of the Scheme of Service for nurses, which was approved in 2016 but still has not been gazetted nearly a decade later. Without this formal guideline, many nurses are paid inconsistently across states, and career progression remains murky and arbitrary. Imagine working for years, only to find your salary and promotions depend more on state policies than on merit or qualifications.

Even worse, judgments by courts, such as the National Industrial Court of Nigeria (NICN)’s ruling in 2016 on nurses’ welfare, have simply been ignored by authorities. And promises of modern healthcare facilities and adequate staffing are made year after year but rarely fulfilled.

The frustration is so deep that many nurses and doctors now see “JAPA” as a rational survival strategy rather than a mere choice.

Government’s Response: Steps Forward, But Are They Enough?

To its credit, the government has recognized the growing crisis and started taking steps — but these efforts, while welcome, are not yet enough to reverse the tide.

Prof. Pate pointed out that the government has doubled training quotas for health professionals to ensure a larger workforce and is trying to address the uneven distribution of medical staff across Nigeria. Policymakers are also banking on the belief that training more health professionals might convince some to stay — and possibly lure some back home in the future.

Additionally, the government introduced the National Policy on Health Workforce Migration, aimed at managing the emigration of health professionals more strategically. The policy suggests offering better incentives to those who remain in Nigeria and using bilateral agreements to control recruitment from abroad. It’s a step in the right direction, but it will only succeed if matched with real improvements in salaries, working conditions, and hospital infrastructure.

A Deeper Problem: Quality vs. Quantity

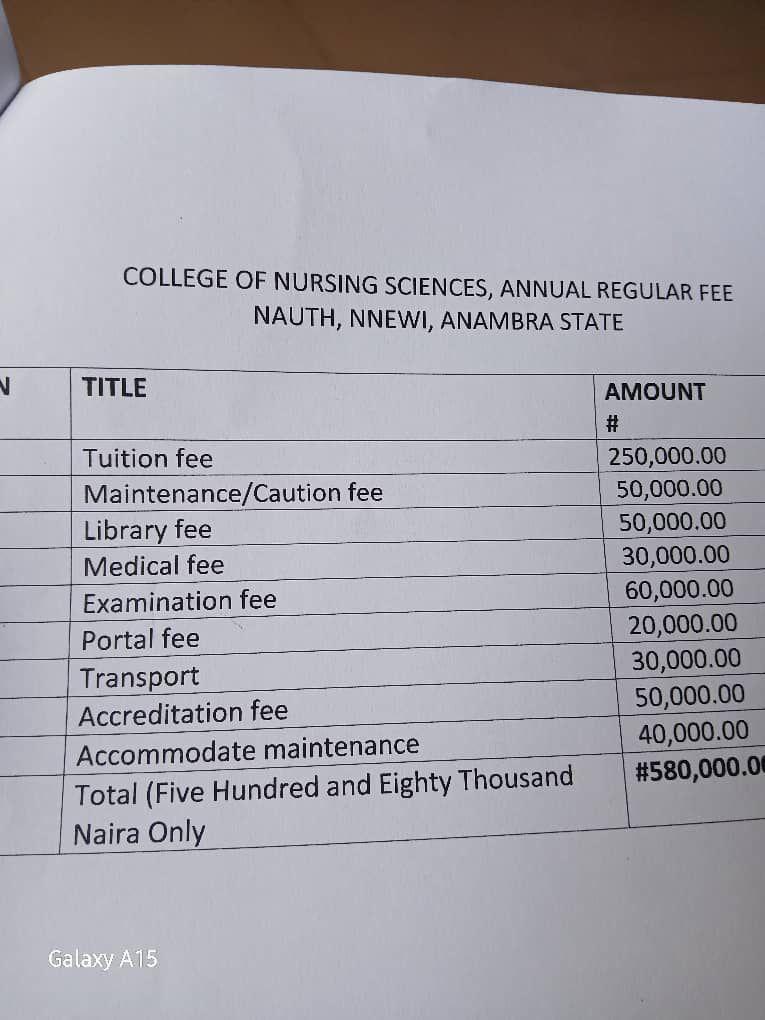

But the solution to Nigeria’s healthcare brain drain cannot be reduced to simply producing more doctors and nurses. As the NANNM rightly cautions, the proliferation of nursing schools without proper oversight and funding will do more harm than good. Churning out graduates without offering them jobs or fair pay will only deepen the problem, breeding frustration and, potentially, unlicensed “quack” practices.

The root of the problem isn’t the number of health workers, but the quality of their work environment. Professionals are not leaving the country just for higher salaries; they’re leaving for systems that value their training, offer clear career growth, ensure safety, and recognize their contributions.

Until Nigeria addresses these fundamentals — including regular reviews of allowances that haven’t changed in decades, clear promotion pathways, modern equipment, and safe, secure workplaces — the “JAPA” wave will continue.

The Way Forward

If Nigeria is serious about retaining its health workers, the solution starts with listening to their voices. The unions and associations representing nurses, doctors, and other professionals have offered clear, actionable demands: improved pay, better infrastructure, secure workplaces, and the implementation of court rulings and policy agreements.

Simply opening more nursing and medical schools without fixing these issues is a cosmetic solution. The real fix lies in creating a health system where professionals are proud to stay and serve, not desperate to leave.

The loss of health workers is more than a staffing problem — it’s a reflection of national priorities. If we want our health sector to survive and thrive, Nigeria must treat its health professionals like the essential heroes they are, not as expendable assets.

Only then will we begin to reverse the tide of JAPA.